Today I’m delighted to host Vanessa Gebbie who’s on a blog tour to celebrate the paperback publication of her novel, The Coward’s Tale, first published by Bloomsbury last November.

The Coward's Tale is the first novel from Vanessa, who is also the author of two vivid collections of short stories from Salt, Words from a Glass Bubble, and Storm Warning, as well the contributing editor of Short Circuit: A Guide to the Art of the Short Story (Salt).

The Coward’s Tale is a striking novel: set in a mid-century Welsh-Valleys mining town, it’s a mosaic of vivid stories concerning the inhabitants, told by the old beggar Ianto Jenkins to anyone who’ll listen. But there’s one story he hasn’t told, his own – until, that is, he’s finally prompted by his friendship with young Laddy Merridew, an unhappy little boy who has come to stay with his granny in the town. It’s a story which strikes at the heart of the town, concerning a disaster in the past, the collapse of the ironically named Kindly Light pit, and which, when he finally tells it, brings together all of the stories. It’s very clever, the way Vanessa brings together so many threads, and the novel is striking too for the distinctive voice in which it’s told – both demotic and lyrical, a voice that’s been compared to that of Dylan Thomas – and the sheer inventiveness of the tales, which, while concretely vivid, have something about them of magic or miracle.

This is a novel about the redemptive power

of storytelling, and, inspired by its striking images and motifs, I asked

Vanessa about her own considerable storytelling powers:

TOFFEES

EB: Ianto Jenkins tells his stories to the cinema queue, but only if they’ll give

him a toffee or two. ‘Stories need fuel, they do,’ he says. What is your fuel

for telling stories, Vanessa, and what do you consider your reward?

VG: Hmm, interesting question. I think my main

fuel for telling stories is firstly that I love stories - and maybe I am

telling them to myself? But secondly the possibility that someone will listen

to it, or read it. While I am writing, I rarely plot - so in a way the story is

telling itself to me as I type alongside - and that can feel really exciting

even though it doesn’t happen nearly often enough! I want to share that sense of discovery with others. There

is, for this writer, no point in writing for a filing cabinet, or a hard drive.

Even if I was only given the opportunity to have work ‘out there’ years after

I’d gone, I think I would still write - actually, it would be blissfully

liberating. (Although someone would have to work out the payment issue while I

was still around, please!)

My reward is feedback from readers. It

doesn’t come often, in the form of written feedback, but I’ve been lucky enough

to have a couple of letters from complete strangers who’ve read The Coward’s

Tale - and the fact that

they have been moved to write and tell me how much they’ve loved it, is

wonderful fuel.

But I also love toffees... and

liquorish...just like Ianto.

EB: Me too re liquorish. I must say it all took me back to my own childhood in Wales when we were all the time dipping into bags of sweets (terrible for our teeth - and how did we ever manage to eat our meals?!). There was a real sense of authenticity about the book in terms of those details. My Welsh Mum read it too - I bought her a copy of the hardback for Christmas. And the detail that amazed her was the smell of the lead blacking when an oven heats up. She said she'd forgotten all about it and you brought it right back, and it was just so right in conjuring up the atmosphere of that time!

WOODEN FEATHERS

EB: Icarus Evans the Woodwork Teacher has striven all his life to do the

seemingly impossible, to carve feathers out of wood so light they will float.

(And, magically, in the story it turns out to be not so impossible.) The novel

too has a magical quality, but I read that you worked hard, like Icarus, to

perfect and polish the prose. How long did you work on this editing stage, and

how much store do you set by that kind of editing graft when you write?

VG: Ah there is nothing magical about the

answer to Icarus’s question, really.

The answers are under our noses, most of the time, we just don’t see

them!

I finished the first complete draft in

January 2010. I’d reached my own

limit, and needed help to polish and strengthen the structure, so it wouldn’t

be just a ‘novel in stories’ much as I enjoy those, but a different beast. With

an Arts Council Grant for the Arts, I was able to pay for a period of mentoring

with the wonderful novelist Maggie Gee, whose own work is so beautifully

structured and lucid, I knew I had a lot to learn from her. She was (and is!) incredibly generous. We’d

meet and she’d give painstakingly detailed feedback on the manuscript and I’d

go off and work on it - I was very disciplined! She might comment on the prose, and I’d always marched up

and down reading it out loud - so

more of that got done.

In the end, every paragraph, every

sentence, every space, got reassessed during that time, either by us both, or

by me, in the course of the general revision.

When my agent sent the novel out, he said

‘they are either going to go for it as it is, or not at all...’ and he was

right. Because I’d worked so hard

on edits over some nine months in the end, give or take (my Dad died in the

middle, so there were some months were nothing much got done at all, I hope

understandably...) there were not many tweaks to make when it came to preparing

the manuscript for publication

with Bloomsbury.

I work hard at my writing, as I know you

do. There was a time when I thought my early drafts were terrific, with a

bounce and a buzz that was easy to kill with too much tinkering. But now, I’ve

learned to approach editing in a more subtle manner, and hopefully, I don’t

edit the life out as I go.

FISHING:

EB: Matty

Harris, the Deputy Bank Manager, fishes obsessively

in the river for the elusive big fish, while Half Harris, the ‘half-wit’

brother he won’t acknowledge, fishes for random objects. But it is Half Harris

who catches the fish. How often does it happen for you that a story you’re

writing is different from what you planned? Did that happen at all with this

novel?

VG: Oh golly, constantly. I don’t plot and

plan. I follow a vague shape, and see what happens to make the clay as it were,

and I shape it later. As I said above, I see writing as telling myself a story.

If I know what’s going to happen, why bother writing it?

I remember being told once, ‘if the writer

isn’t surprised by the story, the reader sure as hell isn’t going to be...’ or

words to that effect. That is so true!

But back to the editing question - I suppose the skill is to keep the

surprise, whilst smoothing...

DIGGING AND SILVER LEAVES:

EB: There are some mysterious goings-on

in the town, as well as some seemingly weird behaviour. James Little, the old

Gas-Meter Emptier, digs his allotment by moonlight, and every year Judah Jones

the Window Cleaner collects the silver leaves that fall from the trees in the

park and disappears with them off into the church. While this makes them seem

odd, even weird characters, both turn out to have very good reasons. How do you

feel about your characters as you write?

VG: I think people are endlessly interesting.

Even the most seemingly ordinary people have oddities and quirks if you look

closely enough. As I write, I am

very close to the characters. I care hugely about their predicaments - even

though the predicaments are something I must have put them into. I hang around until they’ve extricated

themselves, like walking to the shops behind your four-year-old, hidden behind

trees, just to make sure he’s OK. There are always reasons why people do things

- reasons why we are as we are - one layer of The Coward’s Tale is peeling away

that first layer, to show that, hopefully. It’s so easy to make a snap

judgement about someone - and

usually, that leads to the wrong conclusion, don’t you think?

EB: Most definitely. And the book definitely does that: pulls away those layers to show the sometimes surprising truth about people in moving ways.

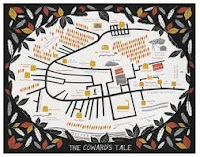

MAPS:

EB: Bloomsbury

made you a lovely musical map of the town, which can be seen and heard here - and which also appears in the paperback edition. How concrete a map of the town did you have in your head as you wrote? There’s

also a theme of maps in the novel: can you comment on the significance of the

fact that Tutt Bevan the Undertaker is looking for a straight line through the

town, a true line that maps, with their complicated boundaries, can’t tell?

VG: Bless the lovely Alice Shortland at

Bloomsbury, who came up with the idea, and put my husband and I through our

paces over a whole weekend, while I tried to draw the street pattern I

remembered from my childhood stays in Merthyr, and he played the artist!

Basically, no - I had no map. I just wandered in my memory down real streets,

into real kitchens, front rooms,

back gardens and parks. But

the memories of childhood places are shifted by time, aren’t they, and

by competing memories. So in the end I put a note in the back to that effect.

“I have moved mountains, I have shifted your streets,” basically - in case

anyone got upset at what I’d done to their town.

VG: Bless the lovely Alice Shortland at

Bloomsbury, who came up with the idea, and put my husband and I through our

paces over a whole weekend, while I tried to draw the street pattern I

remembered from my childhood stays in Merthyr, and he played the artist!

Basically, no - I had no map. I just wandered in my memory down real streets,

into real kitchens, front rooms,

back gardens and parks. But

the memories of childhood places are shifted by time, aren’t they, and

by competing memories. So in the end I put a note in the back to that effect.

“I have moved mountains, I have shifted your streets,” basically - in case

anyone got upset at what I’d done to their town.

It’s hard to comment and explain what Tutt

is doing - in a way, explanation deadens it, possibly? All I know is, his

grandfather dealt with a death by going on a journey - and Tutt is perhaps

dealing with his own coming twilight (literally, too, as his sight is weak...)

by trying to do the same?

But also - specifically talking about

Tutt’s journey, don’t we try to iron out all the twists and turns of life, to

make things simpler for ourselves? Like Icarus, he sets himself an impossible

task. At the end of that tale - there is an answer, again, although maybe not

what he was expecting!

Following a map stops us taking unexpected

detours and discovering new places... that’s so true. Look at Sat Nav - half

the time I have no idea where I’ve just driven. I’ve just gone where I have

been told.

TUNNEL:

EB: The old railway tunnel is the scene of another disaster, the death of a child, but also in the end the scene of closure for the bereaved mother. The novel doesn’t shrink from darkness, yet is full of humour and in the end redemption. Can you talk a bit about this, and the role of story-telling in overcoming grief?

VG: Life is a glorious mix of light and dark,

isn’t it? I have great faith in the strength of the human spirit to make the

best of things - but sometimes, don’t we need a bit of help to do that, in the

form of a mirror, metaphorically, so we can see ourselves and our situation

reflected back at us? Stories are

that mirror. In stories, as we

learn about characters, don’t we also learn about ourselves?

I have read in many learned places how

stories are important as they teach us to empathise with others. Without them,

we become centred on self, perhaps - I like to think the airing of the stories

in The Coward’s Tale is one way in which the community begins to understand

itself, and takes a step towards healing itself.

Howzat for philosophy?

Elizabeth, its been great - thank you so

much for hosting a stop on the tour, and thanks for such searching questions.

EB: And thank you so much, Vanessa, for stopping by and giving us such great insights into the process behind your very distinctive and moving novel.

Readers: do give yourselves a treat and read The Coward's Tale if you haven't already. And Bloomsbury are offering a free copy for one lucky winner: just say in the comments below if you'd like to be put in the draw.

If you don't win, or can't wait, it can be ordered from here.

The previous stop on Vanessa's tour was over on Jen Campbell's blog, and tomorrow she will be with Charles Lambert discussing the novel's story of a same-sex love and its theme of the elusive question of human happiness. Details of the complete tour can be found here).

EB: And thank you so much, Vanessa, for stopping by and giving us such great insights into the process behind your very distinctive and moving novel.

Readers: do give yourselves a treat and read The Coward's Tale if you haven't already. And Bloomsbury are offering a free copy for one lucky winner: just say in the comments below if you'd like to be put in the draw.

If you don't win, or can't wait, it can be ordered from here.

The previous stop on Vanessa's tour was over on Jen Campbell's blog, and tomorrow she will be with Charles Lambert discussing the novel's story of a same-sex love and its theme of the elusive question of human happiness. Details of the complete tour can be found here).

7 comments:

Loved the headings, the questions and the insights.Thanks!

Vanessa+ Elizabeth, thanks for another lovely post. The book + characters sound more + more intriguing as you blog hop, slowly building into a crescendo: "I want that book, I must have that book!"

Dora, I'll put you in for the draw, shall I? And Merc, would you like your name to go in too?

Yes please!!! I'm in the process of writing a book from a child's perpective, that takes place in a small town + I think Vanessa's book will be wonderfully inspirational + instructional. Besides, the book sounds magical + different + I wish Vanessa much success.

That's done, then! The Coward's Tale is certainly inspirational. And good luck with your book, Dora.

Lovely interview. The book is definitely on my wishlist. Put me in the draw too please!

Will do, Carys!

Post a Comment