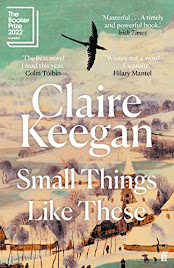

Everyone in the reading group did agree that it was extremely well written if somewhat conventional in style, and, as Clare (who had suggested the book) said, vivid in its depiction of the small-town community and its culture of secrecy and constraint. All appeared, like me and my writing colleagues, to have read it in a sitting. However, I was surprised that everyone in the group beside me and John had some quibble or other, sometimes quite radical.

The novella centres on the figure of Bill Furlong, the town's coal merchant, and chiefly takes his third-person viewpoint. Brought up in the big house of a Protestant widow after her unmarried maid became pregnant with him, Furlong is now married and focussed on providing for and nurturing the talents of his five daughters who attend the Catholic school, 'the only good school in town', and take music lessons at the convent next door to the school. He has never found out who his father was, but supposes that it must have been one of the many middle-class visitors to the big house.

Christmas is approaching, and there are large orders of coal, and Furlong must make a delivery to the convent. The nuns at the convent run a laundry - well used and appreciated by the town's businesses and hospital - as well as what is understood to be a training school for young women. Little is known about the latter - at least in Furlong's understanding - and various rumours surround it, some saying it is a place for girls of low character to be punished and reformed, others that it is a mother-and-baby home for 'common' girls and that the nuns make good money out of having their babies adopted.

Furlong hasn't in the past liked to believe any of those rumours, and indeed has shown little interest, but one evening in the recent past he arrived too early with a coal delivery, and with no one to meet him, wandered into a garden and a chapel, where he encountered clearly browbeaten girls on their knees scrubbing. One girl dared to stand and begged him to take her to the river, where she could end her life, and when he refused, to take her home with him. The shocked Furlong refused once more, before they were interrupted by one of the nuns. Leaving, he noted things that one might associate with a prison: a padlock on an outside door, the way the nun locked the door behind her just to come out to pay him, and jagged glass embedded in the inner garden wall. At home, Eileen, his wife, told him to drop it, forget it, think of their own girls. Furlong couldn't see what their own girls have to do with it, although he did wonder, What if one of their own were in such trouble?

As Christmas approaches Furlong is feeling a vague existential unease, but he is a practical man, not having been given to speculation or making connections, and can't pinpoint the cause of his feeling. He takes his load to the convent, rising before dawn. He unbolts the coalhouse door and finds a young girl crouched inside, barefoot and weak and coal-blackened, the excrement on the floor showing that she has been there for longer than just one night. He takes her, stumbling, to the convent door, and as they wait there she asks him if he'll ask the nuns about her baby who has been taken away from her. The Mother Superior exclaims at the girl's foolishness in getting herself trapped in the coalhouse while 'playing', and insists Furlong comes in for a cup of tea.

Furlong's mother is long dead - she died when he was a teenager - but the farmhand Ned, on whom he relied as he grew, is still living at the big house, and Furlong, having heard he isn't well, decides to pay him a Christmas visit. He finds Ned isn't there, but in hospital, and the girl who answers the door assumes he is a relative of Ned's, saying she can see the family likeness. And a light is suddenly shone on the matter of Furlong's paternity.

Christmas Eve arrives. When Furlong goes to pay for his mens' Christmas dinner at the local cafe, the female cafe owner makes clear she knows about what she calls his 'run-in' with the Mother Superior, and warns him that the nuns 'have a finger in every pie'. He should watch what he says about what goes on up there, she says, as he could damage his daughters' chances at the school.

His work for the year done, he wanders through the town. He thinks of the extent of Mrs Wilson's kindness in saving his mother from the convent, so much greater, we are now to understand, when the father was none of her of circle but her farmhand. He thinks of how he refused the girl who asked him to take her to the river, and how he failed to ask about the coalhouse girl's baby as she had asked him to, and 'how he'd gone on, like a hypocrite, to Mass'. He keeps walking and goes on up to the convent, passing through the open gates to the coalhouse. He pulls back the bolt, and, as he clearly suspects, the same barefoot girl is imprisoned once more inside.

The book ends as Furlong is walking with her back through the town towards home, people staring or avoiding them. Ahead of him is all the trouble for his family that this will cause, but Furlong has done the thing that, if he hadn't, he would have regretted for the rest of his life.

Introducing the book, Clare said that she felt that Furlong had been used as a device in order to write about the Magdalene laundries. This statement left me taken aback, since the focus of the novella is not the Magdalene laundries as a subject in itself, but Furlong's psychological journey in relation to them. Later, Doug or Mark, or both, would say they felt unsatisfied that the novella ends where it does, that the real interest would be the consequences of Furlong's arriving home with the girl from the convent. Doug did agree however when I said that the interest of the novella was not so much what happens, but Furlong's psychological and moral progression (from lack of interest and identification with the goings-on in the laundry, to an understanding of his own early situation and the need to pay back the kindness that was done to him and his mother). Doug said he wasn't sure he found it convincing that Furlong, a practical, non-thinking man, would understand so quickly over his cup of tea with the Mother Superior that she was lying about the girl in the coalhouse, or that it was in character that he should consequently make a wilful point of hanging on when she tries to get rid of him. Or indeed that he would return to the convent to rescue the girl. Again, however, Doug agreed when I said that what alerts Furlong on the first occasion is a realisation that the Mother Superior, in asking significantly about his daughters' studies at the school and the convent, is making a veiled threat (to prevent him from talking about the coalhouse incident), and that it is the revelation about Ned and the consequent extent of the kindness that had been done his mother that prompts his final action.

Thinking back now, it occurs to me that the problem was that our group is very used to discussing novels (we don't do short stories), but this very short novella, written by an author who has only ever written in the two short prose fiction forms (short stories and novellas), uses very much a short-story mode, that is, the mode of glancing implication. It is never actually spelled out that Furlong has either of these revelations. The most that is replicated of Furlong's realisation about Ned is 'It took a stranger to come out with things'. This narrative mode of implication, it seems to me, is very potent in conveying the atmosphere and tenor of a society where things are indeed not stated, where secrecy and blind-eye turning are the norm, and truths thus easily buried. To Furlong, the implications of his own past having been buried, the connections are not obvious, but arrive subtly, 'stoking his mind'.

Someone said they felt Furlong was a bit of a cypher, not fully developed, which shocked me, since the substance of the book is basically Furlong's psyche, and Mark said that he felt the most underdeveloped character was Furlong's wife Eileen. I can only think that such criticisms come from a desire for the more objective, detailed and wide-ranging character depiction novels can provide, but which in my view is not the province of the shorter form. This novella too is internal; everything is filtered through Furlong's interiority, and Eileen appears only as she does in Furlong's thoughts.

Someone said, 'But this is only one person!'' (being rescued from the convent), implying, I think, that the book didn't address the real (and real-life) problem of so many young women and their babies being virtually disappeared. This left me dumbfounded, as, as far as I am concerned, the force of fiction is indeed that it can address the universal via the emotional impact of the particular, which to me this novella does indeed do.

Someone wondered why the author had chosen a male protagonist (presumably for such a female-orientated subject), until the rest of the group decided that a woman would never have been in a position to do what Furlong did. Ann said she found the novel anachronistic. It is set in the 80s, she said, but felt like the 50s (it was noted that semi-rural Ireland in the 80s was indeed like the 50s: witness the fact that the Magdalene laundries closed only in 1996), yet there is a reference to crows picking at takeaway pizza boxes: pizza takeaways would not have arrived in Ireland by the 80s. As a result, she said, she lost all faith in the book and didn't want to go on reading. Clare added that Furlong was anachronistically feminist in that when the Mother Superior suggests he must be disappointed that none of his children is male, he stands up for women. At the time of the discussion I found myself convinced by this, but having looked again at what he actually says - 'Sure didn't I take my own mother's name' and 'What have I against girls...? My own mother was a girl once' - I'd say that this is based in his realisation of what is going on in the convent, and how narrowly he and his mother escaped that fate. The burgeoning feminism implied seems to me a legitimate and believable response to his realisation. Sexism was of course dominant in the 80s, but it does not seem to me unbelievable that such extraordinary circumstance could prompt a man's developing feminist consciousness, even in small-town Ireland at that time. It seems to me that, rather than simply using a male character to facilitate a plot, as was suggested, the author's project is specifically to chart this growing male consciousness, and that this is indeed the novella's dynamic strength.

Finally, Doug said to my shock that he was surprised that the book had won all the prizes it had.

On the evening of our discussion I was suffering with shingles and was feeling pretty low, but I don't think it was just that that left me feeling a bit helpless to argue. Rather, I think, it was sheer surprise at these criticisms of a book that I - and John - had found frankly stunning.

Our archive discussions can be found here and a list of the books we have discussed, with links to the discussions, here